Judgement in the Age of Conversational AI

Why Finished-Looking Answers Are Dangerous

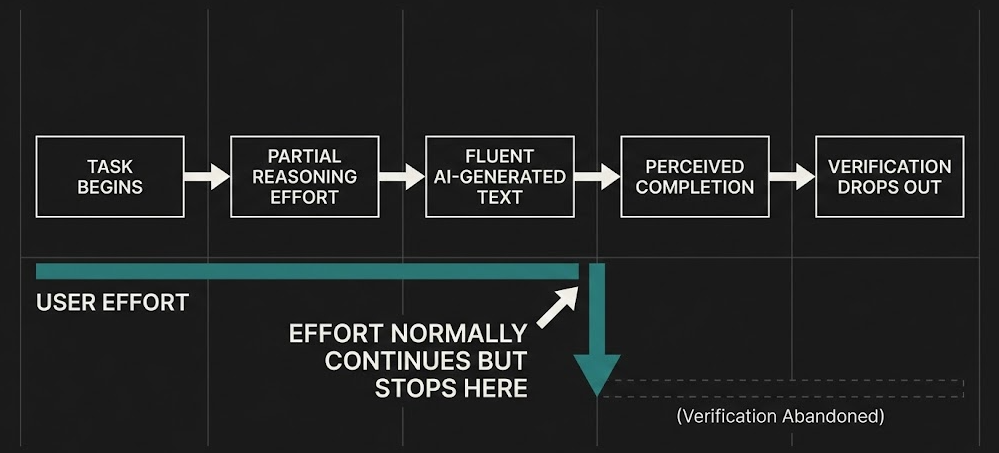

Conversational AI shortens thinking by making completion feel earned - It does this even when the underlying judgement is thin.

The prevailing response treats this as a literacy problem. People misunderstand how language models work, so they trust them too much. Explain that these systems predict text rather than retrieve truth and the risk recedes. That account is tidy and largely wrong. Many users who understand the mechanics still defer to fluent outputs when pressure rises. The problem does not begin with belief. It begins with how humans decide when enough thinking has been done.

Fluency is a cue

In human judgement, effort has always played a signalling role. Difficulty suggests importance. Slowness suggests risk. When reasoning feels strained, people remain alert. When a task resolves quickly into a coherent form, attention drops. Conversational systems remove precisely the friction that used to keep judgement open. The answer arrives shaped, balanced, and complete. No contradictions surface unless they are requested. No gaps announce themselves. The mind reads the artefact and infers that the work has reached its natural endpoint.

That inference is rarely conscious

An individual example makes the point without drama. A financial analyst reviews a draft risk note produced with assistance from a language model. The text is well structured, cautious in tone, and uses the right vocabulary. The analyst scans it, adjusts a sentence, and sends it on. They do not re-examine the assumptions behind the risk rating, partly because the document no longer feels provisional. The fluency of the prose substitutes for the unease that would normally trigger a second look.

This is not persuasion - It is closure.

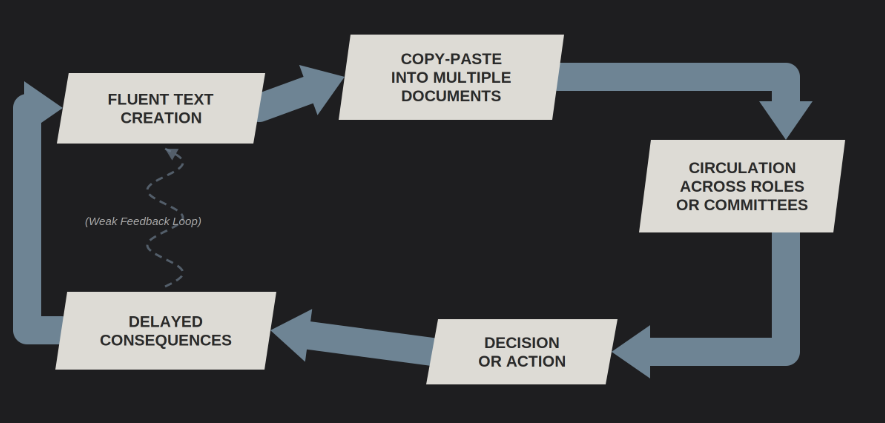

The same dynamic appears more starkly once text begins to circulate. A university committee paper is assembled from several inputs, some human, some generated. The final document reads smoothly and cites familiar concepts. During review, discussion focuses on phrasing and alignment, not on evidentiary gaps. Weeks later, the paper is referenced as if it reflected settled analysis. By then, no one can say which claims were supported, which were inferred, and which emerged from synthesis. The artefact has outlived the scrutiny that should have accompanied its creation.

Figure 1 — Fluency acting as a stopping cue in individual judgement

What makes this difficult to resist is that the interaction rewards the user immediately. Time is saved. Anxiety falls. The output looks professional. In environments where speed and presentability are valued, these signals dominate. The cost of pausing to interrogate the reasoning is immediate and visible. The cost of being wrong is deferred and often diffused.

Learning is affected in quieter ways. When answers arrive fully formed, users reconstruct less. They retrieve less. They test less. Over repeated interactions, the sense of competence shifts. Confidence grows, but it is anchored to performance with assistance rather than to internalised judgement. When conditions change, that confidence travels badly.

None of this requires the system to be inaccurate.

The risk is amplified when outputs are reused. Copying text into emails, reports, slides, and submissions extends the life of the initial judgement while weakening its traceability. Each reuse strips away context. Each handoff delays accountability. By the time consequences appear, the origin of the claim is obscure. Responsibility is shared thinly enough to feel like it belongs to no one.

Figure 2 — Circulation of fluent artefacts and delayed accountability

This does not affect all work equally. Where feedback is fast and stakes are low, errors surface quickly. Informal learning recovers. The danger concentrates in domains where evaluation is indirect, decisions are layered, and outputs are treated as inputs for further reasoning. Education, policy, finance, healthcare administration, and governance share this structure. In these settings, fluent artefacts accumulate authority simply by surviving.

Calls for better training miss the point if they assume that knowledge alone will counteract convenience. People already know that polished text can be misleading. They still accept it when the environment rewards moving on. The issue is not moral weakness or technical naivety. It is a mismatch between how judgement actually operates and how work is organised once fluent assistance is available.

What would need to change is uncomfortable to articulate because it challenges institutional habits. Tasks that matter would need to remain visibly unfinished for longer. Claims would need to carry their evidentiary weight with them as they move. Completion would need to be harder to confuse with correctness. These are design problems, not exhortations.

Until then, fluent text will continue to function as a stopping rule - It tells people, quietly and convincingly, that thinking has reached its end.

Whether that is true is often discovered too late.